Greek vase collecting boomed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries due to intellectual curiosity, a shift in ideological values, and the perceived artistic importance of the vases. Wesleyan’s vase collection includes mostly South Italian vases likely found in a funerary context, ranging from utilitarian wares to more decorative mythological scenes, along with a select number of vases of potentially Attic origin.

Antiquities collecting in particular boomed during the Renaissance. This was a period of rebirth having to do not just with the Christian faith, but also with the ‘reclaiming’ of Ancient Rome, and later Greece. Initially Rome was the focus of antiquarian interest and study, partially because Greece was comparably inaccessible. Through reading the writings of the Romans, Renaissance era humanists sought not only to tap into the traditions that they valued, but also to make them their own. For example, Ovid became moralizing. Ovide Moralisé, written in the fourteenth-century, was based on the Metamorphoses and equated the characters with biblical figures, also using the stories as examples of what not to do in order to lead an appropriate life.

There has been a widely held assumption that Greek vases were not collected until the eighteenth-century. A more accurate supposition is that while they were collected before then, it was mostly as a side-dish to the more highly valued sculpture. One reason that vases became popular is that they were more financially accessible to potential collectors. The prices did rise once the scholarly interest in Greek vases was fully cemented. Greek vases also functioned as a link to ancient Greek paintings that had been lost. This came on the back of the 1827 discovery of painted Etruscan tombs that was seen as secondary evidence of the paintings of the Greeks lost to us now, but alluded to in literary traditions.

The emic nostalgia that was a factor in Greek vase collecting created the desire to own anything that would create a connection to that past. These vases can be broken down into three categories that relate back to nostalgia. The potentially Attic vases are a potential link to the origin of Greek vase painting. Those that have typical South Italian iconography link very directly and visibly into the vase painting tradition.Finally, those in the mythological or scene-type tradition are also indicative of other parts of ancient Greek culture that collectors could have been seeking connection with.

The collection was donated to the University in 1900 by Mrs. W.E. Gilbert, whose husband, Mr. William E. Gilbert, acquired the vases in Sorrento, Italy. Some accounts of the acquisition specify that he purchased the vases as they were being excavated from tombs. Neither Gilbert had a direct connection to Wesleyan, but it is suggested that the Methodist history of the school was a factor.

Black-glazed skyphos

Potentially Attic origin, 575-475 BCE

Ceramic

1900.2562.42, collected by Mr. and Mrs. W.E. Gilbert

This vase is assumed to be of Attic origin based on the deep black glaze and high quality of the clay. The glaze is applied unevenly to the surface and is patchy in areas. It is in very good condition. The potential for counterfeit should be considered. This skyphos would have been valuable to collectors due to their connection with the original Greek vase painting tradition. Ancient Greece was felt by many Europeans to be their cultural history. In trying to reconnect to what they thought was the source of the best intellectual and artistic products, then it makes sense that a collector would have been interested in a direct link to the Attic tradition of vase painting.

Black-glazed lekythos base

Potentially Attic origin, 480-400 BCE

Ceramic

1900.2562.28, collected by Mr. and Mrs. W.E. Gilbert

This vase is assumed to be of Attic origin due to the dark black glaze that has been applied evenly to the lekythos. The glaze has no metallic shine and the clay is of high quality. Stamped lekythoi are thought to be export items and are rare on mainland Greece. Due to it’s excellent condition, the potential for counterfeit should be considered. It would have been valued for it’s direct link to the Attic vase painting tradition.

Detail: shows break.

Detail: moulding.

Lid with wave pattern

Protocampanian, made in Southern Italy, 350-300 BCE

Ceramic

1900.2562.3, collected by Mr. and Mrs. W.E. Gilbert

The wave pattern is one that shows up frequently on South Italian vases – and is seen on many of the other vases in this collection. Similar to the Hopi pottery with kachina designs, this was a common motif on pottery that could help to identify it of South Italian origin. This lid would have been good examples of decoration within the South Italian tradition, and could have been valued for that fact.

Black-glazed kylix

Potentially Attic origin, date unknown

Ceramic

2003.45.1, unknown collector

This vase is assumed to be of Attic origin based on the fine quality of the clay as well as of the glaze. There is little information known about this vase – it is potentially from the Gilbert Collection but was separated after the closing of the old museum. Due to it’s excellent condition, the potential for counterfeit should be considered. While perhaps not as visually arresting as some of the South Italian material presented in the exhibit, this vessel nevertheless forms a direct connection to an artistic tradition from which South Italian pottery is once removed.

Red-figure lekanis lid

Campanian, made in Southern Italy, 350-325 BCE

Ceramic

1900.2562.10, collected by Mr. and Mrs. W.E. Gilbert

The wave pattern is a common motif on South Italian pottery. Similar to the small lid above, the distinctive quality of the wave pattern on South Italian pottery makes the lekanis lid valuable to collectors.

Top view 1900.2562.10

Black-glazed lekanis

Protocampanian, made in Southern Italy, 350-300 BCE

Ceramic

1900.2562.26, collected by Mr. and Mrs. W.E. Gilbert

The wave pattern is a common motif on South Italian pottery.

Detail: wave pattern.

Red-figure bell-krater with heads of women

Campanian, made in Southern Italy, 335-315 BCE

Ceramic

1900.2562.15, collected by Mr. and Mrs. W.E. Gilbert

Vases depicting the heads of women were very popular in the South Italian painting tradition. The heads are thought to represent Aphrodite, Nike, or sometimes Persephone. Attributed to the Danaid Painter, the subject matter and profile of the woman are distinctive.

Red-figure hydria with Eros

Paestan, made in Southern Italy, 325-310 BCE

Ceramic

1900.2562.17, collected by Mr. and Mrs. W.E. Gilbert

Attributed to the Boston Orestes Painter, this vase depicts Eros, wreathed, with his foot propped on a rock. The spotted rock is indicative of South Italian painting and is a representation of volcanic rock. This motif is most common in vases of Campanian origin. This type of localized decoration might have increased the vases worth to collectors looking for a holistic collection of South Italian pottery. The hydria also falls within the mythological tradition. Its connection to myth would have made it more appealing to collectors who valued the intellectual history of the Greeks.

Side view 1900.2562.17

Detail: spotted rock.

Red-figure squat lekythos with mistress and maid scene

Campanian, made in Southern Italy, 360-330 BCE

Ceramic

1900.2562.22, collected by Mr. and Mrs. W.E. Gilbert

The “mistress and maid” scene has been typified since 1942. The scene features two women interacting with one another, usually with one, the mistress, receiving something from the other, the maid. It shows up on a number of shapes, but most commonly on lekythoi. In particular, it is common on Athenian white-ground lekythoi that were used as funerary offerings. It is attributed to the Whiteface Painter (AV I).

Side view 1900.2562.22 showing mistress.

Side view 1900.2562.22 showing maid.

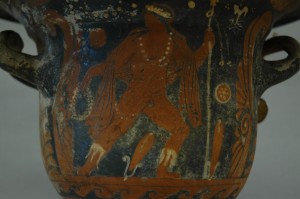

Red figure bell-krater with Dionysus

Paestan, made in Southern Italy, 315-285 BCE

Ceramic

1900.2562.24, collected by Mr. and Mrs. W.E. Gilbert

Dionysus is a common mythological figure on South Italian vases. Here he is depicted holding a wreath in one hand and a thyrsus in the other. The other side features a seated maenad. Theatrical scenes were largely depicted on South Italian vases, and Dionysus was portrayed also for his link to theater. It is attributed to the Painter of Naples 1778.

Detail: Dionysus holding a wreath and thyrsus.

Detail: seated maenad.