The collecting of Native American art in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was driven by exoticism, nostalgia for times past, and westernized specialized production as an offshoot of the two. Europeans and North Americans who collected Native American objects in an attempt to connect to their cultures do so from the position of a cultural outsider – driven by an etic nostalgia. The Melville collection is a comprehensive collection of Hopi and Tewa materials and the objects chosen exemplify collecting practices.

Exoticism informed the collecting of both the missionary, who intended to show the primitive nature of other cultures, as well as the ethnologist, who methodologically collected other cultures with the intent to preserve. Professor and Mrs. Melville hold a middle ground between these two types of collectors. On sabbatical from Clark University, the Melvilles spent three weeks living in Polacca, Arizona. The purpose of their collection was to record the life that they encountered in Polacca.

The small bowls shown here with a kachina design are slightly older than the material in the Melville collection and are utilitarian wares collected by Matilda Stevenson, a Smithsonian ethnographer who collected while accompanying her husband a US Geological Survey – sent by the Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE). At one point, her husband James notes that their collection in its totality weighs 10,512 lbs – this fits with the narrative of overzealous collecting in early anthropology. The BAE set out to furnish a National Musuem, and did not yet need to be as discerning about their collecting practices because this marked the beginninf of collecting Native American cultures – and collectors wanted evidence of anything and everything. The The large bowl was collected around the same time by either Cosmos or Victor Mindeleff while they, too, were working in the Southwest for the BAE.

Ideas of exoticism tie into feelings of nostalgia for what Western visitors to reservations saw as a simpler time. Mrs. Melville expressed similar feelings: “There is a subtle charm about the Hopi and their high perched homes that is particularly delightful. No other place in our land affords such an opportunity to observe native Americans living as they lived before Columbus came.” These statements demonstrate the patronizing opinion held of Native Americans as belonging to prehistory. Currently, museums struggle with how to convey Native cultures without rooting them so deeply in ‘tradition’ so as to deny people the right to identify without regard to ‘tradition’.

A large portion of the Melville collection was purchased directly from the craftsmen or at trading posts in Arizona. During the early twentieth century, as tourism extended into the southwestern United States with the spread of railroads, the market for Native American art grew. With this came the advent of ‘tourist art’, created specifically for purchase by tourists. Often this meant the creation of goods that catered to the desires of the Western consumers, for example the cowboy hat ashtray. Not an authentic shape, and perhaps now perceived as kitsch, it was popular with tourists.

The Melville collection was donated to Wesleyan in 1976 by Mrs. Melville at the suggestion of her grandson, Robert Arnold (Wesleyan Class ’69). Along with the pottery and other Hopi and Tewa material, there are large amounts of records associated with the collection, including an extensive photographic collection. Wesleyan accepted the donation as a teaching collection – promising to keep it intact and only ever release it to another non-profit institution.

Bowl with polychrome Kachina design

Hopi Culture, made in Moqui, Arizona, 1870-80s

Ceramic

1897.1168.11, collected by Matilda Stevenson

This bowl is historic utilitarian material collected by ethnographer Matilda Stevenson. It was then brought to Wesleyan when it was exchanged with the Smithsonian for beetles and minerals. Informing ethnographic collecting is the idea of an other – an example of etic thinking. The preservation of Hopi and Zuni cultures for the future was a goal of the ethnographers – but this came with the implication that the cultures were soon to become obsolete. There are other elements of these vessels that might have made them compelling to collectors, as well.It features a kachina mask on the inside, something that collectors could point to as “identifiably Indian.” This was appealing to the collectors seeking to connect to a Native American past driven by etic nostalgia through the lens of exoticism.

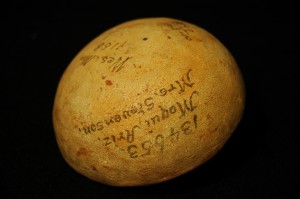

Detail: polychrome bowl with kachina design

showing old Wesleyan Museum number,

Smithsonian accession number, name of collector,

place of collection, and current catalogue number.

Side view of 1897.1168.11

Bowl with polychrome Kachina design

Hopi Culture, made in Moqui, Arizona, 1870-80s

Ceramic

1897.1168.10, collected by Matilda Stevenson

Similar to the bowl above, this was also collected by ethnographer Matilda Stevenson and then was traded to Wesleyan. It also features a kachina mask on the inside, situating it within the tradition of collecting for the exotic nature of an object.

Side view of 1897.1168.10

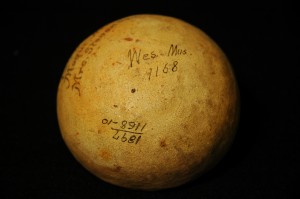

Detail: Polychrome bowl with kachina design.

Smithsonian accession number, place of collection, name of collector.

Detail: polychrome bowl with kachina design.

Old Wesleyan Museum number, current catalogue number.

Cowboy hat ashtray

Hopi Culture, made in Arizona, 1927

Ceramic

2003.5.18, collected by Mr. and Mrs. Melville

The cowboy hat ashtray is a good example of tourist art. It was collected by the Melville’s during their stay in Polacca. It is made in the Sikyatki Revival Polychrome style and was potentially meant for use as an ashtray. The Sikyatki Polychrome style was in its height between 1375 and 1625. There is a tradition of modern potters reinventing older styles – which is what occurred with the revival in the late 1800’s. There is a maker’s mark on the bottom in the form of a spider that identifies the craftsman. The ashtray fits into the narrative of specialized production because it was not an original ceramic shape, but was instead made for purchase by tourists.

Side view of 2003.5.18

Baseball hat

Hopi Culture, made in Arizona, 1927

Ceramic

2003.5.16, collected by Mr. and Mrs. Melville

The baseball hat fits within the same category of “tourist art” as the cowboy hat ashtray above. It may have been functional, but one can only speculate about the purpose of the holes in the head of the cap. One more creative explanation that I have heard is that it was used as a pencil holder. Pieces like this were sold for profit by Native craftsman who were tapping into a new realm of art that appealed directly to Western travelers.

Top view of 2003.5.16

Plaque

Hopi Culture, made in Arizona, 1927

Ceramic

2003.5.58, collected by Mr. and Mrs. Melville

This plaque is reminiscent of the tiles that Thomas Keam and Alexander Stephen suggested to Hopi potters. Keam and Stephen thought that this style of tile painting would resonate well with Western consumers. Painting on flat surfaces was different from painting on the curved surfaces of vessels. The tiles also featured a hole drilled into the top so that they could be hung on walls.

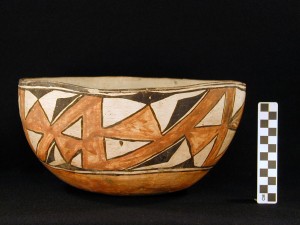

Large bowl

Zuni Culture, made in Acoma, New Mexico, late 1800’s

Ceramic

1898.1264.18, collected by Victor or Cosmos Mindeleff

Collected by ethnographer brothers Victor and Cosmos, this historical material fits into the ethnographic collecting tradition. Both brothers were in the Southwest doing work for the Bureau of American Ethnology and ended up doing some collecting while they were there.

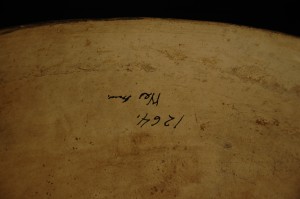

Detail: Smithsonian accession number,

name of collector, and place collected.

Detail: Old Wesleyan Museum number.

Kachina doll “Kuwan” or “Heheya”

Hopi Culture, made in Arizona, 1927

Wood, feather

2003.6.43, collected by Mr. and Mrs. Melville

The kachina dolls serve as a comparison to the bowls – also being “identifiably Indian.” The katsinam (plural of kachina) stay in the village for six months, bringing rain to the land. During these months there are a multitude of ceremonies involving the katsinam, including the Powamuya ceremony – for the new planting season – in February. Kachina dolls are made by the katsinam and then given to the children during this ceremony. They were not meant to be embodiments of kachina spirits, but were used as education tools to teach about the various kachina spirits.

Detail: 2003.6.43

Kachina doll “Umtoinaqa”

Hopi Culture, made in Arizona, 1927

Wood, feather, plant fiber

2003.6.44, collected by Mr. and Mrs. Melville

There is an argument to be made that the dolls were being collected in a more ethnographic tradition of trying to preserve an important religious aspect of a culture. It is unclear whether these dolls were used before they were collected, or whether they were made for the Melville’s as examples of kachina dolls. But given the range of other items in the Melville Collection, it is more likely that the dolls were collected for other reasons like fitting into a Native American artistic tradition.

Detail: 2003.6.44

Hopi boots

Hopi Culture, made in Arizona, 1927

Ceramic

2003.5.80a-b, collected by Mr. and Mrs. Melville

The ceramic boots fit into the tourist art tradition, as well as being decorated with “identifiably Indian” designs (such as the kachina mask on the lower right boot) which would have made them valuable to collectors.

Wall hanging

Hopi Culture, made in Arizona, 1927

Ceramic

2003.5.22, collected by Mr. and Mrs. Melville

The wall hanging is also reminiscent of Keam and Stephens’ tiles which were catered to the tourist art market. It has a hole in the top, evoking the format of the tiles. The wall hanging would have had no practical use to its makers, but worked well as decoration in the homes of Westerners.